Small-capitalization stocks are having their moment in the sun as part of the “ Trump trade. ” Whether they end up having staying power might have little to do with tariffs.

Since the Nov. 5 election, the S&P SmallCap 600 Index is up nearly 8%, compared with a roughly 5% gain for the S&P 500. Top risers include regional bank Dime and car-rental company Hertz, which have market values below $2 billion.

Back in July, Trump’s improving chances for victory, as well as disappointing earnings by some technology companies, had already pushed money into small-cap funds. Yet for 2024 as a whole, the S&P 600 still lags behind its blue-chip counterpart by more than 10 percentage points. Since the end of 2019, the shortfall is almost 40 percentage points.

Catalysts for a more lasting shift are accumulating. The Republican Party’s sweep appears to herald lower taxes, lighter financial regulations and higher tariffs , which Wall Street believes will benefit domestically oriented businesses more than multinationals.

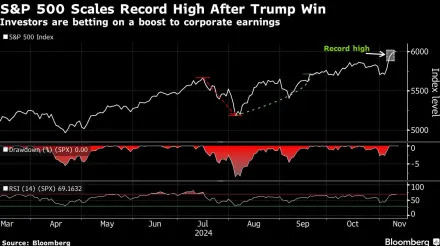

The S&P 500’s gains also have been so top-heavy that its largest 10 companies now make up the biggest part of the index ever.

“When you get this extreme level of concentration, eventually there’s a buyer’s exhaustion,” said Jonathan Coleman, who manages small-cap funds at Janus Henderson.

Finally, the Federal Reserve has started cutting interest rates . Many analysts argue that small-caps are the ideal investment during monetary-easing cycles, as is the case after recessions.

Small-caps should be more than a short-term trade, though.

Looking at a data set by economist Kenneth French that starts in 1926, average five-year small-cap returns aren’t hugely different whether they start inside or outside of these specific periods, especially relative to large-cap performance.

As for politics, their impact is notoriously hard to predict. Tariffs are a particular headache for import-dependent small businesses . Case in point: Small-caps did very well during the turbo-globalization of the early 2000s, yet lagged behind in 2019 as Trump’s first round of protectionist measures actually came into effect.

Instead, the compelling reason to buy these stocks is that, since 2015, small-caps have been cheaper than blue-chips. The S&P 600 now trades at 18 times the earnings generated over the past 12 months, compared with 28 times for the S&P 500, according to FactSet.

According to monthly data by Furey Research Partners going back to 1968, which includes only profitable companies, a valuation gap as large as the one at the end of November has historically led small-caps to outperform over the following five years 96% of the time, and 51% of the time by more than 10 percentage points. This is what happened after the Nifty Fifty era of the 1970s, when blue-chips were massively overvalued, and the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

When it comes to longer, 10-year stretches, smaller companies have been the place to be almost without regard to when investors bought them, French’s figures show. They have beaten out large-caps three-quarters of the time, even after stripping out the bottom 25% of largely uninvestable microcaps. It isn’t because they are riskier: Adjusted for volatility, the result is the same.

This “ size effect ,” first identified by Rolf Banz in 1981, explains why smaller companies have historically traded at higher valuations than larger ones.

It is also a boon for the fund-management industry, because this is one of the few corners of the market in which actively managed funds can still claim to do better than index trackers and charge fatter fees. Between 25% and 40% of small-cap indexes are made up of unprofitable companies, and it has usually been a good strategy to avoid them. Indeed, stock pickers have been able to generate excess returns simply by being benchmarked to the popular Russell 2000 index while aping the S&P 600 , which screens stocks for profitability, liquidity and investability.

On a rolling 10-year basis, the average annualized return for U.S. small-caps in the top 30% in terms of operating profitability has been 14% since 1963, compared with 12% for large-caps of similar profitability and 9% for small-caps ranking in the bottom 30% of profitability.

To be sure, investors can ask reasonable questions about the declining number of high-quality companies found in small-cap indexes, especially at the same time megacaps keep improving their return on assets.

Nevertheless, the case for going smaller is one of long-term commitment, not opportunism.

Write to Jon Sindreu at jon.sindreu@wsj.com